Too often the word scepticism gets used as a synonym for ‘naysaying’, or at its worst, an adherence to a faith-based value to which everything else gets compared, but which never itself goes unchallenged.

The word scepticism actually has at its root, the ancient Greek term skepsis (σκέψις ), meaning ‘enquiry’. To the ancient Greek sceptics, such as Xenophanes and Pyrrho, the most important part was the ability to tolerate uncertainty. Only from this standpoint can enquiry can begin in earnest.

"It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it."1

To really be a sceptic, in the original sense, one must look for reasons both for and against a position. I argue to truly understand a position, and to not throw the baby out with the bathwater, it is best to temporarily don the hat of the believer. Once a charitable case is built, and results are achieved in favour, only then should one change hats, and amount evidence for the negative case. If no positive results are forthcoming, one ought to return to the ‘natural’ state of uncertainty.

Magical scepticism (my term) is the incorporation of creativity and experience into the exercise. Can we have the same experiences and/or produce the same results as those who believe in a proposition? Can we temporarily talk ourselves into it and what does it feel like when we get there? Once the experience has been obtained, preferably on the terms of the believer, only then should it be taken apart, analysed and scrutinised. I will be writing more here about this method in the future. Or you can purchase a copy of my 2023 book Pragmatic Magical Thinking.

https://spirit.aeonbooks.co.uk/product/pragmatic-magical-thinking/95196https://spirit.aeonbooks.co.uk/product/pragmatic-magical-thinking/95196

Before we explore magical experiences however, let’s start with a question that’s a little more concrete, namely: Are unicorns real?

I particularly enjoy this test question, as ‘Unicorns’ have become in modern parlance, a metaphor for something that either cannot exist, or is otherwise so unlikely to exist that encountering one is something akin to a miracle. Therefore a positive ‘win’ would be pretty satisfying. So let’s dive in.

The first unicorns

Unicorn in Latin, simply means ‘one-horn’. So a simple but unsatisfying way to win the debate would be to simply find a creature or creatures with one horn, dust my hands and call the case closed. I do however promise to try harder than that.

Obvious contenders for ‘one-horns’would be Narwhals with their long toothy horn. Common history has it that these horns were often passed off by medieval and later traders to cash in on the unicorn legend (for a time powdered unicorn horn was thought by the credulous to be a powerful medicine). I would prefer that unicorns at minimum be a land creature with four legs, so Narwhals, though ‘one-horned’ will not satisfy me.

The earliest written accounts of unicorns are Greek, using the word ‘monoceros’ (μονόκερως), and grant us our first surprising fact. The original term was not used to refer to a mythological creature. Instead it appears in natural history accounts.

The earliest of these is the writing of Ctesias in the fourth century BCE. In his work Indika (India), he describes wild asses that were fleet of foot, with a single horn about 28 inches long, and coloured white, red, and black. As a Greek physician who served at the Persian court of King Artaxerxes II in the 5th and 4th centurys BCE, It is not thought that Ctesias ever actually visited India. Instead he gathered accounts about India from Persian explorers, Indian merchants and envoys who came to the Persian court.

As Greek accounts often conflated different species of animals compared with our modern classifications, it seems likely that Ctesias’ unicorns were one of the following:

• A horned ass. This is the least likely contender, though in extremely rare circumstances animals can form ‘horn-like’ growths. Here for instance is a woman with a ‘horn’, which is a cutaneous growth.

• A one-horned antelope or goat. Though animals of this type are ‘supposed’ to have two horns, in rare circumstances the horns can fuse. Here’s an example of a naturally occurring goat with a partially fused horn from Iceland

• The Rhinoceros. This animal fits the bill, but isn’t at all like ‘a wild ass’. Having said that, there is an Indian Rhinoceros, and it indeed has one horn. So this could, at a stretch be the ‘original’ unicorn.

For now I think it’s interesting enough that the first accounts of unicorns are zoological descriptions, not legendary or mythical ones. Having said that let’s move forward in history in order to get closer to our modern ideal unicorn:

Figure : For some people this is the ideal unicorn. I could do without the rainbows, the sparkles and especially the plastic.

In the first century AD, Pliny the Elder described a unicorn in his work Natural History. Again supposedly native to India, it is described as a composite chimera-like creature with a stag’s head, a horse’s body, an elephant’s feet, a boar’s tail, and a three-foot-long horn. Similarly to Ctesias’s account, this unicorn was said to elude live capture. Here the unicorn started to have a legendary status as a symbol for an impossible conquest.

Though Greek translations of the Old Testament (Septagint) from the 2nd century BCE mention unicorns, as ‘monoceros’, this is a mistranslation of the Hebrew ‘Re'em’ (רְאֵם), which scholars understand to mean ‘wild ox’, or ‘oryx’, a two-horned desert-dwelling antelope. The latter is the Modern Hebrew meaning of the word.

Despite the mistranslation, the unicorn interpretation was carried over to the King James Bible, giving us hundreds of years of unicorns symbolism within Christian teachings.

Do unicorn have to be horsey?

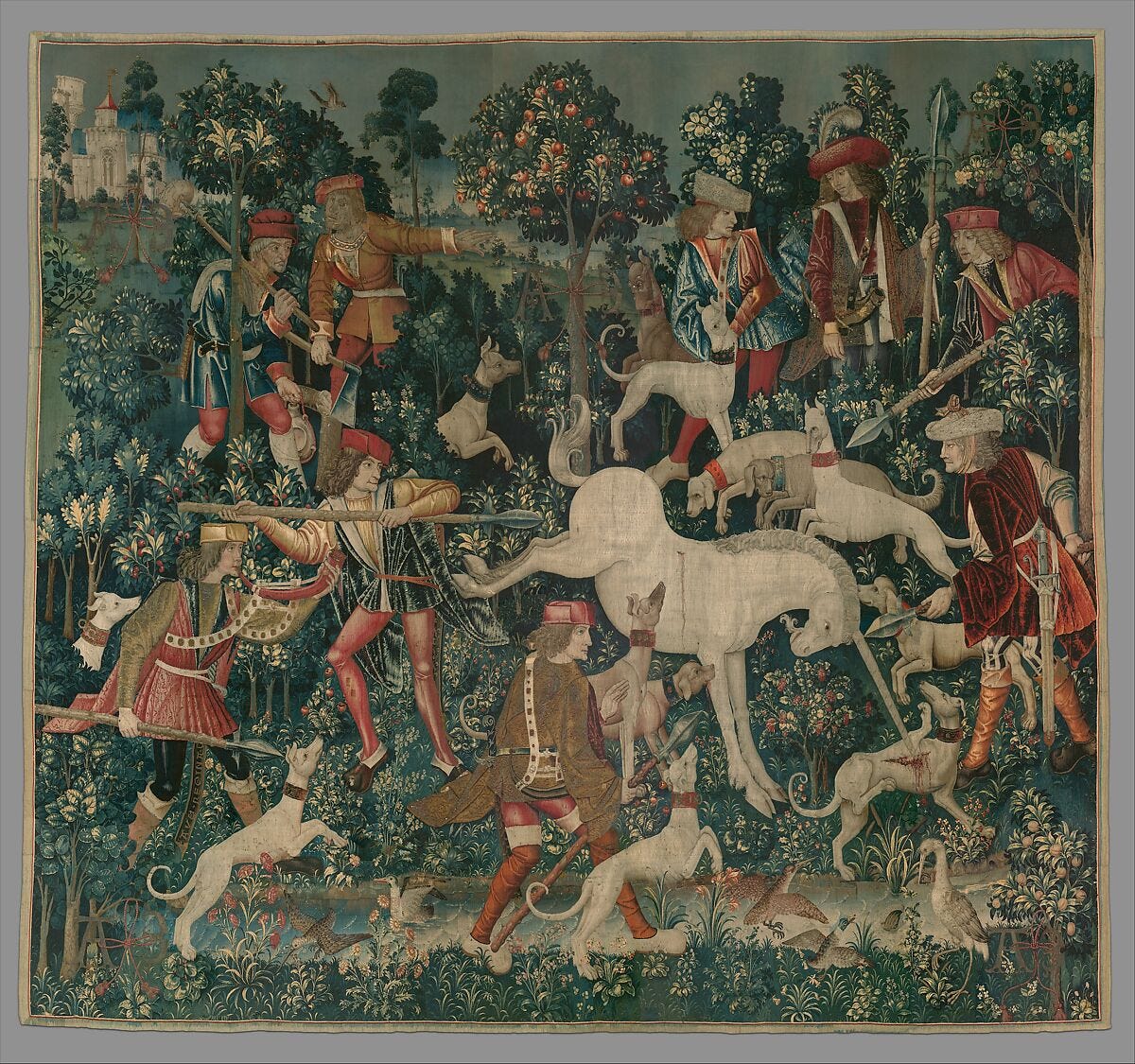

Unicorns became especially legendary during the late medieval period and Renaissance and they were often depicted in allegorical Christian art of the period, as well as in heraldry where they remain a prominent symbol today.

The unicorn was often a symbol for Christ, and was often depicted with a maiden, who represented Mother Mary. In medieval legend it was often said that unicorns could only be caught by virgin maidens. This is almost certainly an inversion of the male hunter archetype, with the unicorn representing the unobtainable quarry. In the Christian mythos, God the immortal Father, has to incarnate through the feminine principle, the mortal Mary. In these depictions the unicorn is always depicted in white, representing Jesus’ purity, lacking ‘original sin’.

Figure : The Unicorn in Captivity (also The Unicorn Rests in a Garden) from the Southern Netherlands between 1495 and 1505.

Many have interpreted the mytheme of the hunt of the unicorn to represent Christ’s persecution by the Roman government.

Figure : Le Vue (La Dame à la licorne) between 1484 and 1500

Figure : File:The Unicorn Defends Itself (from the Unicorn Tapestries)

Figure : A Virgin with a Unicorn, fresco by Domenichino, c. 1604–1605

Note that in all premodern depictions unicorns have cloven hooves and goatee beards. They are also often (but not always) smaller than a horse in size, often appearing in a maiden’s lap, and they very often, but not always, feature a tufted tail, rather than the long tail hair of a horse.

These are all recognisable as goat features. In this way Unicorns are hybrid creatures, part horse, part goat. In some depictions they are hardly horse-like at all. In others they are horses with some goat parts.

Unicorns in heraldry

The other rich source of unicorn imagery that continues to this day is in heraldry, especially in Scotland where unicorns are the ‘royal animal’.

Here is the Scottish royal arms:

Figure : Prior to the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the Scottish coat of arms was supported by two unicorns. However, when King James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, he replaced one of the unicorns with the national animal of England, the lion.

Like wise here is the coat of arms of the United Kingdom:

Unicorns appear throughout European heraldry. Though the hybrid horse/goat version is most common, here is a decidedly goat-like unicorn from the heraldry of Ramosch in Switzerland.

If we account for this evidence, and if we allow our definition of unicorns to include goats, then unicorns exist! Let me remind you of the Icelandic example from earlier:

Figure : The eagle-eyed amongst you will see that the horn forks into two at the tip. Perhaps that makes this a semi-unicorn.

Behold, the reality of goat-unicorns!

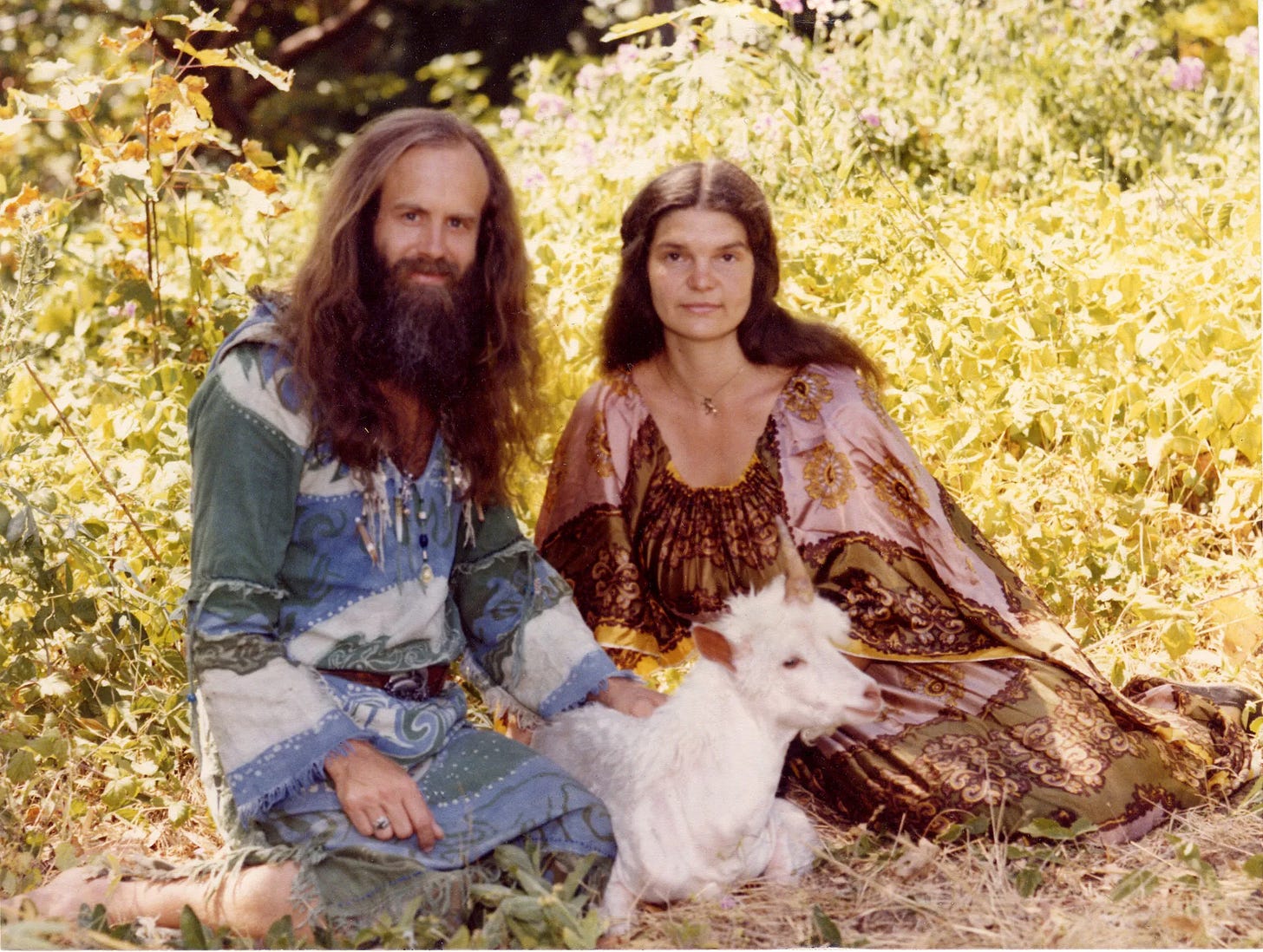

Meet Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, a public wizard.

Born Timothy Zell in November 30, 1942; his magical achievements include:

• Founding the neo-pagan society Church of All Worlds.

• Being a figurehead of the ‘neo-pagan’ movement in the late 1960’s onwards. He claims to have coined the term ‘neo-pagan’ in a 1968 issue of his magazine Green Egg. In my, now somewhat extensive experience with public wizards (including myself) I’ve noticed that most wizards are prone to exaggerate. As it is off-topic, I’ll let him have that one for now. He was certainly a central character of the pagan revival in St. Louis, USA, and beyond.

• Founding a wizard school which is still going, the Grey School of Wizardry. Oberon has now retired as headmaster. As a wizard networker, I managed to help one of their faculty wizards, Noel, get a job there.

• And most importantly for us, Oberon, and his late wife Morning Glory co-founded, in 1977, the Ecosophical Research Association an organisation that explores the truth behind myths.

Oberon created a minor surgery to modify the horn-buds of goats, a technique he was granted a patent for in 1984, and which was based on old animal husbandry manuals. With this he produced a small herd of real goat-unicorns.

“We decided at one point that we wanted to write a book on the subject, of the true stories behind the myths. We have these stories but we don’t know very much about what the stories are about… we started collecting material [from libraries] and one of those critters that we were studying was unicorns and in the process of our research we discovered that unicorns were not a purely mythical beast. We figured initially, they were probably based on a Rhinoceros or something...We found out that wasn’t the case. In fact unicorns were real animals and they looked exactly like they were depicted in all these bas-reliefs and the tapestries and the inscriptions. Those are very authentic, that’s exactly what they looked like…

It became obvious to us that they were different species… Some of them were antelope-beings, some of them were goat-like, some of them were bulls…, deer...What we are talking about is a phenomenon which allows a creature from a species that is normally two-horned to somehow come out one-horned, and it changes everything. The whole animals is completely changed by that. They become more powerful, and magnificent, intelligent and charismatic, everything...In the process of our research we figure out how it was done. This was a thing that was actually practiced by ancient peoples. It was a magical secret that was closely guarded by to produce these incredible animals that would be the herd leaders, and most importantly, able to defend the herd against predators… what about if we decide to see if we can do this?”

In 1980 Oberon and Morning Glory went to stay on a friend’s farm, where they raised up a herd of unicorns. Participating in local renaissance fairs they adopted the roles of Wizard and Witch.

According to Oberon, it is a minor surgery to shift the horn buds of a goat a few days after birth. These buds aren’t initially attached to the skull. Over time the bone of the skull grows into the buds and the horns, anchoring them to the skull, and they emerge from the scalp. Shifting the buds into the centre of the head causes the horns to grow together into one larger fused horn. (Please don’t take this as an advocation on my part, especially if you are part of some animal welfare group).

Oberon’s unicorns became part of public performances and were taken on tour.

Figure : Morning Glory

So where does this leave us?

In agreement with Oberon, I concur that one-horn goats are real, that they are a valid type of unicorn with historical evidence, and that therefore unicorns are real.

In all of my research into magic, the occult, music, creativity and other fields, this type of result is pretty indicative of what one can expect from these types of investigations.

In searching for real examples of things normally deemed ‘unreal’ by a group of people, first you have to play with the definitions. If you let the definitions be defined by the nay-sayers, for instance ‘a unicorn is a one-horned horse that doesn’t exist’, then you are almost never going to get what you are after. Some people will think that this is ‘cheating’, but I suggest that even in the scientific method, phenomena have to be redefined as emerging data changes our concept of what is going on.

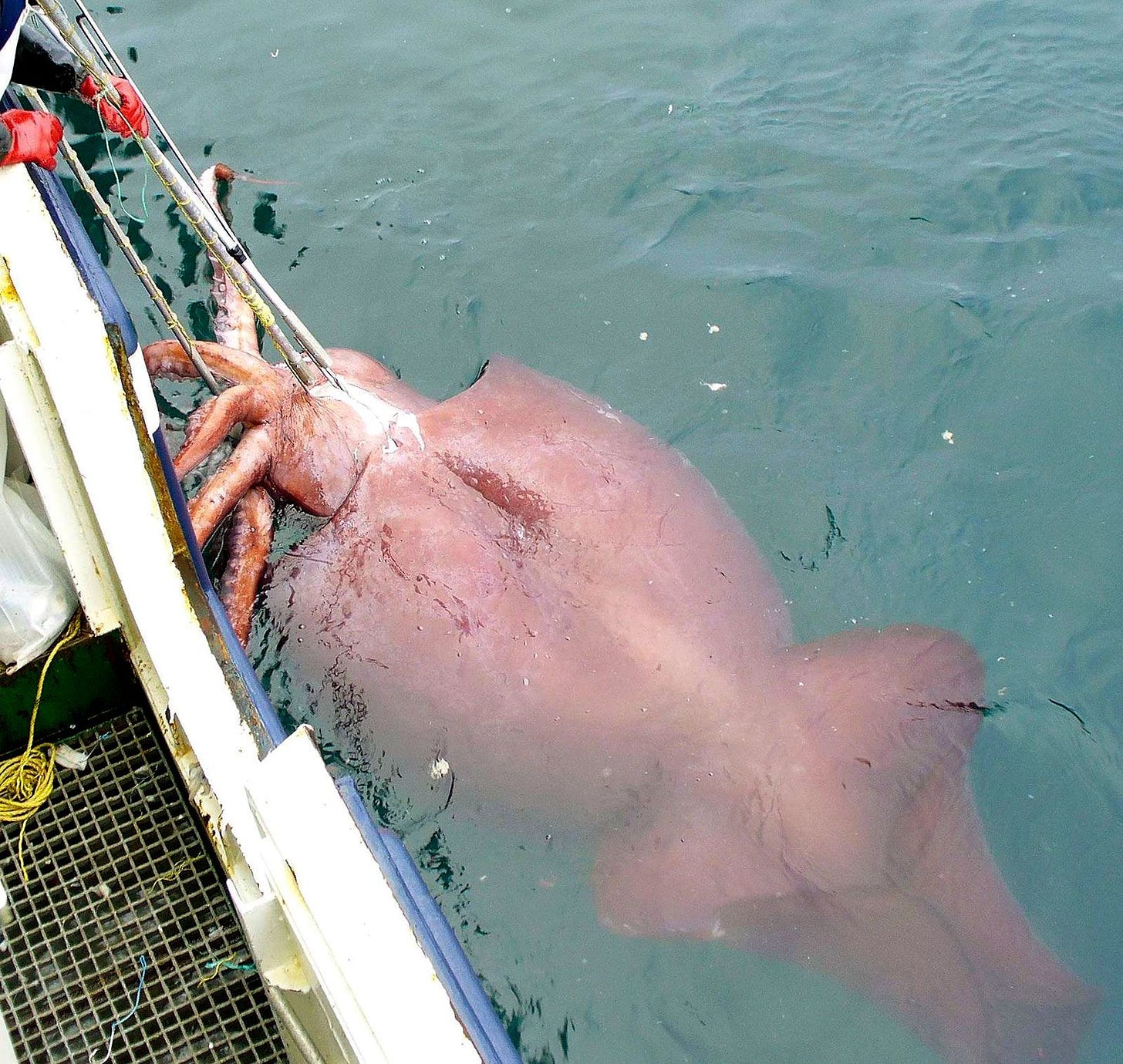

Very often supposedly ‘unreal’ things can actually be found, albeit with a tweak. Krakens are real, as colossal squid. They aren’t as long as a battleship, but they are up to fourteen metres long. Pretty good!

Bigfoot, as a giant ape, probably doesn’t currently walk the earth. However 100,000 years ago a ten foot tall relative of the modern Orangutan, did walk the earth. Scientists have dubbed this creature Gigantopithecus Blacki. It was identified from a tooth being sold in a medicine shop in China. (I wrote a song about it here:

Giant oarfish make pretty good sea serpents. They aren’t as long as an ocean liner, but they have been found at lengths of eleven metres!

The takeaway for me is that the REAL version of a thing, representing something that is truly possible and obtainable, is more interesting than the imaginary version, even though our imagination can generate ideas that are bigger or weirder.

If you are the type of person who agrees, then you have the right attitude to study and understand reality, magic, creativity and manifestation. If you are the type of person who finds non-horsey, goat unicorns disappointing, then you might have to remain in the safe-house of a very limited world.

Meanwhile I’ll be enjoying the fact that unicorns exist. Til next time.

Footnote

1This quote is often attributed to Aristotle. It appears to be a modern paraphrase a quote that appears in his Nicomachean Ethics.